Spoiled for choice

What the right choice of boat is still depends on the individual sailer and his plans. Although the ocean and its requirements have not changed one bit, naval architecture now significantly differs from that of fifty or hundred-fifty years ago – mainly in order to cater to the wishes of all those who have sailing itself not on the top of their list of priorities. A constantly growing number of different concepts for boat-designs make the decision for expectant buyers all but easy, while more often than not disregard the very basics of seaworthiness, which are the result of over 5000 years of ship-building-history.

Many things are said about sailors and the relationship to their boats – a most famous quote claims that the two most happy days in a boat-owner´s life are the day he buys his boat and the other one is the day he sells it again. I can´t agree with that, but I am sure that not only the level of satisfaction between buying and selling the boat is decided with the right choice, but also if that one big storm - that we all know is waiting for us out there - is going to be survivable on this choice. Even those who are not long-distance-sailors, long-term cruisers or live aboards and consider themselves weekend sailors or good-weather-sailers know in the back of their minds that weather predictive services today, although easily available at a finger’s tip in mid-ocean, are still not totally reliable and a surprise in form of a storm can still happen anytime - a seaworthy ship underneath gives peace of mind in any weather, because it is ready for anything that can and will happen.

In the old days there were luggers, brigs and brigantines, topsail schooners and barques among others, and it was confusing for all those not of a naval background, but looking at today´s bluewater-yachts, racing sloops, offshore cutters, cruising cats and deck-salon-trimarans is equally perplexing for even those with a lifelong marine experience. So what happened, apart from diversification?

Joshua Slocum and Sir Francis Chichester, who famously sailed single-handedly around the world – the first in 1895-1898 and the second in 1966-1967, had boats that were built first and foremost for seaworthiness – although people who sailed Chichester´s “GIPSY MOTH IV” say, she was built a little bit too much for speed. Slocum`s “SPRAY” inspired many naval architects and is still built and sailed in many replicas. As a third vessel for these examples, I choose the “JOSHUA” - named after Slocum - by Bernard Moitessier, who famously abandoned the victory in the 1968 first solo-nonstop-round-the-world-regatta, shortly before the finish and choose to sail on instead. And of course as a fourth example I cannot help but compare the ship I captain myself – “SV NAILAH”. What do those boats have in common and what distinguishes them from today´s designs?

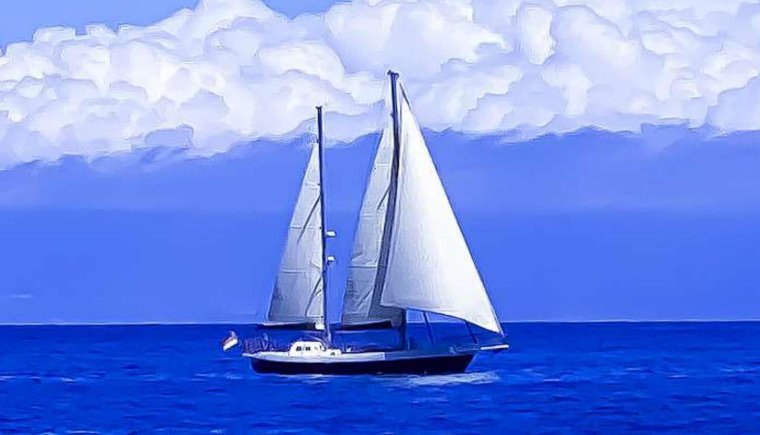

SV NAILAH under three slightly reefed sails in the North Atlantic - 2023

First of all: they are all two-masted, - given that in the case of Slocum`s “SPRAY”, it was a later addition - and all three of them were long-keeled, which in combination made them - compared to contemporary designs - very true to track. A very important feature, especially for single-handed or short-handed crews. Well balanced ketches like Moitessiers “JOSHUA” or “NAILAH” can sail hours or days on end without a helmsman, an autopilot (which will break sooner than later), nor even a bungee tied to the wheel. Two masts also distribute the sail area on more, but smaller sails, which are one by one easier to handle.

What all those boats do not have - among other things - is neither a waterline longer than the deck, nor a bathing platform, nor windows - not even portholes - in the hull, nor a companionway like a terrace door, nor four cabins with four bathrooms with four toilets. This begs the question: Why did boats change so fundamentally? These changes cannot be explained easily, since they are not based on technical developments. In 1895 Joshua Slocum had everything needed to give his “SPRAY” a waterline longer than the deck by adding a sugar-scoop-stern, which also would have made it easier for him to install a bathing-platform. Why didn’t he? Why didn’t Chichester have windows in the hull of “GIPSY MOTH IV” or Moitessier not have a sliding terrace-door in the companionway of his “JOSHUA” or why does “NAILAH” only have one toilet? The simple answer is: Over 5000 years of shipbuilding-history and the resulting experience.

What changed when and is it a healthy development? In the 1970s for example the reverse or sugar-scoop-stern made its appearance to a broader public. The regatta-rules of the day categorized boats into different classes by the length of the deck, so when the waterline was elongated beyond the end of the deck, the boat would be in a smaller boat class, but sailing and winning with the longer waterline of a larger boat class. It was basically in order to cheat the regatta-rules, but soon everybody wanted to look so sporty (or like a cheat to those who knew the reason) … nowadays this reverse stern with an integrated bathing-platform seems to be the gold standard in contemporary boat designs. Ketch “NAILAH” as well as the three other, more famous examples, have neither reverse sterns, nor bathing-platforms. While in some very short moments I find myself being jealous of those who do have one … when lowering the dinghy for going on a dive or when cleaning the blood of a caught fish out of the deck’s treadmaster-covering. But then I remember what my personal plan for the boat was, and it did not include diving or fishing to an extent that the seaworthy form should adapt to those rare moments. “NAILAH’s” priority is sailing, cruising, passaging anywhere at anytime in the most safe and convenient manner possible – bathing, diving and fishing have to be adapted, not the other way around.

A friend of mine said “All those modern boats look good in the harbour … but that’s not what boats are made for!” well, that only is partially true, since actually the majority of boats today are made to look good in a marina. A boat-builder, working in a well-known company for sail-boats, told me a couple of years ago about the surprising findings of their market-evaluation and it goes like this: Most boats sold are chosen by the owner’s wife or spouse and their main criteria is: How many of my girlfriends can I invite on our new yacht and have them all stay in their own cabins with their own bathroom and their own toilet. Only then on second place is how good the boat looks in the marina - sailing characteristics or seaworthiness comes further down the list. “… but that’s not what boats are made for!”

Reverse sugar-scoop-sterns of different shapes and sizes - 2024

Half a ton of potted plants on a catamaran - 2024

A sliding, glass terrace door on a 62ft Mono-Sloop - 2024

Statistically, the number one reason for boats to sink is the toilet … that is the more complex answer to why “NAILAH” only has one toilet with tubes looping well over the waterline. And as far as good looks go - seaworthiness and beautiful lines do not have to exclude each other - whenever “NAILAH” has one of her very rare stays in a port, there are people on a daily basis walking to the far side of the marina in order to have a closer look, often even a feel of her (is that really steel?) and are always eager to give compliments on how beautiful she is.

A sailors sailboat

Sailing Vessel NAILAH of Berlin is a go-anywhere-at-anytime ketch, drawn by Dutch navalarchitect Dick Zaal in 1984 after plans of the legendary Norwegian boat-builder Colin Archer. NAILAH is a heavy displacement long-keeled double-ender made in a Dutch ship-yard in 1997 from 7mm Lloyds-approved ship steel, weighing in at about 35 tons when fully loaded. She is high-rigged to fly six sails of about 200m² sail-area in fact she is so high rigged that even her mizzen mast is longer than the overall shiplength of 60ft, needing a counterweight of eight tons of led in her long keel in order to give her a sufficient righting momentum.

SV NAILAH in San Miguel, Tenerife - 2024

NAILAH further has a beam-to-beam engine-room, tanks for 1.5 tons of diesel and 1.5 tons of water, an 8kw-generator, seawaterdesalination, diving-compressor, central heating and so on… and no, sorry … she is not for sale!

Obviously, her priorities are neither representing in a marina nor winning any regattas. I wanted a seaworthy ship that is capable to cope with any sea-state in any condition and can do that for a very long time autonomously. Three days into her maiden voyage a 45knot gale whipped up 15-18ft/5-6m waves in the southern bay of the North Sea and convinced me of her epic abilities – I never looked jealously at any other boats since and decided to cross the Bay of Biscay in October (something the books tell to avoid at all costs) without blinking an eye – she sailed nine knots over ground, while beating into 40knots of wind and 12ft/4m waves.

So why are ships like her not build any more …? One of the most renown companies for building cruising-ketches announced in the previous year that they will build single-mast boats only from then on. Why would they do that? Why give up on all the experience of generations of boat-builders and follow a fashion, like they did fifty years ago, when introducing the sugar-scoop-stern. It is not only that the market is spoiled for choice, it is that the market is spoiled – period. Most builders don’t want to take risks and most of today’s sailers don’t want to abandon all the amenities they have at home – aboard they want room for a large barbecue-grill, an even larger flat screen TV, potted plants and throw-pillows. Forgotten seem the millennia when seafaring meant to face the worst mother nature can dish out and to - at least temporarily - abandon the safety, comfort and abundance of landlife.

Seafaring thereby earned itself the reputation of relentlessly building the character of seagoing men and women.

The right choice of boat changes naturally if one is based in the San Francisco Bay area with its gusty high winds or in the calmer and more predictable Maine, or based in neither of the two but with plans to visit both. I naturally write for and to those who, like myself, want to visit both and many other different places where they will encounter a multitude of conditions.

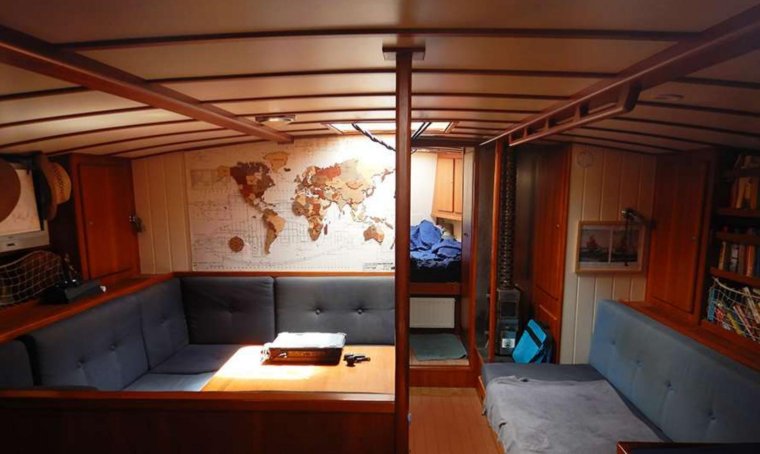

Robin Lee Graham was 16 when in 1965 he set sail on his 24-foot sloop “DOVE” to circumnavigate the globe … it is possible, but I bet if Graham were given the choice, he would have gone for something a little bit bigger. A rule of thumb says the boat should offer one foot of boat-length for each year of the owner’s age, and it is certainly true that the older one becomes the less willing one gets to bend and crouch below deck. And being comfortable aboard is not a luxury - it is essential for endurance and safety, since one is going to tire more easily and tend to make wrong decisions when uncomfortable. On the other end of the spectrum is too much space and yes, that seems to be a thing nowadays. I met a delivery crew of a brand-new 72ft designersloop, priced at a minimum of 2.5 million English pounds with the very basic features only. Although winner of a lot of the many yacht-of-the-year-awards, the crew was not happy with it, because of: too much space! Below Deck, they said, the designers created a large salon at the expense of less storage space and seem to completely have forgotten the addition of handlebars, grips or poles for bracing oneself in heavy weather. So after some injuries the delivery crew had to stretch lines back and forth below deck in order to be able to move without falling from one side of the salon all the way to the other side – it seems to show that modern boat-designs can be surprisingly dangerous if actually taken out on the ocean and sailed for real. NAILAH has lots of room below her 16ft or 5m wide deck, but naval architect Dick Zaal chose to fit her with lockers that are up to four feet deep, leaving a generously measured mess that still features handlebars and poles everywhere.

NAILAH’s wide mess has enough space to live, yet none to fall about

More than in any other field I know, with sailing the devil is in the detail. So to-be-sailors, future boat-owners and expectant buyers should pay attention to details. It is easy to imagine oneself on this or that boat, anchored in turquoise waters in front of white beaches with wild palm trees … but people seem to rarely imagine themselves on the boat while getting to those beaches - through treacherous waters, towering waves, high winds and busy traffic-separation-zones.

SV NAILAH anchored in front of a beach in Fuerteventura, Spain - 2022

From a long-distance-sailor’s point of view, details start with the choice of material: Classic in wood, sturdy in steel, ultralight in carbon fibre, or light and strong in aluminium, unconventional in cement or now very conventional in fibreglass – already the materials can make the choice difficult.

Wood is only classic when (like in the case of “GIPSY MOTH IV”) mahagony, oak, teak or other slow-growing hard woods are involved - then wood can be quite durable and at the same time easy to work with, but as a biological material, shipworms, bore-worms and barnacles are a serious threat in tropical waters, so wood will need a lot of caretaking and maintenance while the whole boat is out of the water. Modern wood in form of so called laminated naval plywood came a long way, but still is rather for an afternoon on the lake, a little optimist or the transom of an inflatable dinghy than for serious long-distance passaging. In the first Golden Globe Regatta solo-non-stop around the world in 1968, there were two plywood trimarans and both did not perform satisfactory, started leaking, drawing water and finally disintegrating after only several months at sea. Not my choice on and for the long run.

Steel is the choice of material for basically all professional seafarers – all trawlers, tugboats, tankers are steel and for good reasons: Steel is lasting, sturdy, rugged and easy to maintain … but to clear up a common misconception: Easy to maintain does not mean maintenance-free. On every steel ship, there are vast supplies of `easy to use´ metal brushes, sandpaper and hardcover-paint. When tended to properly, steel boats can last well over fifty years. And while they last, they can take a real punishing. I talked to a captain who admitted to slamming his steel-schooner into a reef with seven knots, and all he had to do in order to repair the damage was to apply a new coat of antifouling. This sturdiness comes with a price paid in mentioned easy but time-consuming work, hard currency and weight. Designer-boats from fibreglass for two and a half million quid are the exception from the rule, but usually steel-boats are a bit more costly in purchase, but then again, they retain their value better and live longer. And steel is easy to repair, since there is probably not even a small fishing port without someone there who can weld steel. Last but not least: Steel is the heaviest of the materials and consequently steel-boats need a good, high rig with lots of sail area in order to achieve sufficient speeds, but are always going to be slower than comparable boats from lighter materials.

Carbon fibre and other ultralight materials are equally pricey, yet so light and presumably sturdy … well, they are light, but they are not all that sturdy. When in 2007 Captain Pete Bethune tried to beat the world record of the fastest circumnavigation in his carbon fibre motor trimaran, he encountered almost the same problems after only several weeks which the plywood trimarans in the 1968 Golden Globe race faced after several months. Leakages, drawing water and finally starting to disintegrate. Carbon is great for the sailing sport, but it is not the material of choice for the long-distance, long-term sailor. One can only imagine what forces act onto the structure of two-digit-tons of boat when beating into wind and waves for days or weeks on end. Carbon fibre at best is for cruisers who tend the stay in front of the wind with following seas, reducing stresses onto their boats greatly.

Aluminium is supposed to be light and strong - the perfect combination of the cheaper steel’s and more expensive carbon’s properties, and under normal circumstances it probably is more long-lasting than steel since it does not oxidize as badly - but then there is the low melting point of aluminium, making it notoriously hard to weld or to find someone who can properly weld it. I actually considered aluminium as an alternative to steel, until I saw pictures from forest-fires in California, where cars got caught in a blaze. The cars´ steel-bodies were still recognizable as Chevy or Volkswagen, yet of the aluminium wheels were only puddles from molten material left.

Cement seems to be a counterintuitive and very unconventional material to build boats from. And while it is hard to find statistics about the materials used in infamous incidents, like the 98`Sydney-Hobart- or 79`Fastnetrock-regatta-tragedies, it is almost impossible to find reliable statistics about cement or concrete boats, as it is hard to find them on sale or to find people who can talk about their cement boats - the reason to all being that there are still only very few of them out there. Whenever I met owners of concrete boats, I asked them about their experiences and both of them were very happy with their boats and the material although admitting it was hard to repair, once broken.

Fibreglass is the most conventional material used in the building of recreational boats today. And therein already lies the problem… recreational sailing means a Sunday afternoon going up and down in front of the harbour and being back in before dinner. On other occasions it may even mean a whole weekend of sailing along the coast. But actual passage-making is not recreational. For a shorthanded crew or a single-handed sailor, the five day trip it takes to passage to Bermuda from Virginia or to the Canary Islands from mainland Spain is maybe an exhilarating adventure, most likely a mental and physical challenge and most definitely lots of hard work and dedication, but it is not recreational or relaxing in most cases until anchored in St. George or Lanzarote. But there are many fibre glass boats crossing the Atlantic almost daily – that is right, but in the previous ARC 2023 (Atlantic Rally for Cruisers) of the abandoned boats, all were fibre and all were modern boat-designs.

And even if seven-knot-crashes into reefs are not planned and arecavoidable through good navigation, there also are 3000 shippingcontainers going missing at high seas every year and there are other unpredictable encounters, too.

In 1973 the 30ft-yacht “AURALYN” was accidentally hit by a surfacing 36ft sperm-whale and sank in the north-east Pacific. The couple sailing until then on “AURALYN” spent 117 days in a life-raft before being rescued. In 1981, another suspected whalecollision sank the yacht “NAPOLEON SOLO” on an Atlantic crossing from El Hierro to the Carribean, forcing its skipper to spend 76 days of his crossing in a life-raft. In the previous year sailingyacht “JAMBO” sank after a collision with an `unknown object´ in the Atlantic, its skipper was fished out by a container-ship after just 24 hours. Even if internet-access, sat-phones, EPIRB (Electronic Position-Indicating Radio Beacon) and AIS (Automatic Identification System) make passage-making safer and the rescue quicker, but a material that can handle encounters with containers, whales or reefs seems to be the more reasonable choice, at least when leaving sight of the coastline for more than a couple of hours.

Once the preferred material is chosen, a suitable form for the material should be found, and here it gets even more complicated.

First there is the question of the amount of hulls. Multihull catamarans and trimarans have distinctive advantages not only when sailing in regattas, but these advantages rarely and if, then only difficultly translate to cruising, passage-making or longdistance-sailing.

60ft super-heavy Mono vs. 55ft ultra-light Multi - 2024

Multihulls distribute their weight on more keels, so they have less draught, producing less drag on the hulls – this is the secret of their superior speed compared to monohull boats and this is one advantage that can translate to cruising, but … cruisers and especially liveaboards tend to have their whole life with them on the boat and in addition also provisions, spare-parts, tools, and some amenities like a diving-compressor and a generator. The more weight is accumulated, the more the multiple hulls sink into the water, the less speed-advantage a cat or tri can deliver until they are as slow as a mono. The largest company to produce catamarans designed cruising-cats that are built to be packed full of live-aboard supplies and then sail at rather normal speeds. Other, smaller companies try to keep their lines streamlined and their interior super-light-weight, and I know cruisers who then limit themselves to a minimal amount of stuff they carry around and thereby keeping the advantage of a multi even while living aboard with a wife, two kids and a dog. I also heard of crews that are so ‘Gung-Ho’ that the whole crew cut off the handles of their toothbrushes in order to save weight. Different strokes for different folks…

Another advantage is the stability of multihulls compared to monos, and multis actually do not lean and do roll less, although they pitch the same - so this is a true advantage – especially for people who cannot deal with too much movement, because of motionsickness.

But this is an advantage that is only true until it isn’t - when a multi starts leaning due to strong winds, it becomes extremely unstable, even volatile … but not to worry: once it capsized and turned turtle, it becomes very stable again – in fact so stable that it needs a crane to right it up again.

In 1989 the trimaran “ROSE-NOELLE” was flipped upside down by a rogue wave and the crew drifted on the hull for 119 days before being finally swept ashore on New Zealand’s Great Barrier Island, where nobody believed their story until the police examined the wreckage and found several months worth of barnacles had grown on the mast.

That does not mean multis are unsafe – on the contrary, since all multis have multiple engines, which is a massive safety-bonus. And finally the advantage that definitely translates into all kinds of cruising or passage making: Space! Even shorter multihulls have enormous room, although many of them lack proper enclosed storage-lockers, the room inside a multi is always more generous and spacey compared to a same-size mono.

A clear disadvantage for single- or short-handed crews is that multis almost never have multiple masts, which means that the one mainsail needs to be so big that it is hard to be handled by a single person without technical help – and all electric or hydraulic winches will (just like the autopilot) break sooner rather than later. And last but not least: for multis, there is double the price to be paid in most marinas.

Monohulls on first glance seem to have many disadvantages in relations to multis, yet many of these supposed disadvantages are actually beneficiary when inspected more closely. The stabilityissue is a very obvious one. Although the monos seem so much more unstable with their rocking and rolling, it actually is this ability to rock`n´roll that makes the monos more stable in the end. If a sudden gust hits a mono on the broadside, it will lean over to as much as 90 degrees or even more, but after the gust has passed, or the sheets have been let out, the mono will right itself again and again and again if necessary – this self-righting is particularly true for long-keeled boats and an often overlooked safety-feature of monohulls that multis are in a total and often dangerous lack of.

A definite advantage from a single-hander´s point of view is that other than multihulls, monos come in a variety of fractional riggings with multiple masts, such as schooners, ketches or yawls – making it very well possible to sail solo on a large boat of 70ft or more if one chooses to do so. Monohulls also come in a greater variety of materials, although there is the rare plywoodor aluminium-oddity, multis usually come in fibreglass only, while monos of all kinds are available in all materials. While the only choice for multis seems with or without deck-salon, monos come in a much greater variety of forms, as well as with or without decksalon. For multis, there is basically just one form of stern and it is a bathing-platform times two … unlike for monohulls, where there are transom- and pinky-sterns, long and short double-ended canoe-sterns, counter-sterns with and without overhang and it does not end with the modern reverse- or sugar-scoop-sterns. The same applies to the deck form with trunk- or flush-decks, deck-salons or pilothouses, center- or aft-cockpits – with monohulls, there is just a multitude of variations and combinations to choose from.

Stern-view from a 2020s- and a 1960s-boat - 2023

With monohulls, the decision-making does not end above the waterline. There is still the form of keel to choose. While multis do not have any real choice in the form of their underwater-ship, monos have the same multitude of variations under water as above.

Classic sailing-ships have a long keel that starts at the bow and ends at the propeller and rudder, which are placed at the very end of the ship - traditionally and out of necessity due to physical laws concerning leverage … but many things have changed rapidly in the past 50 years and a lot of developments, variations and new choices have found their way from high-performance sailing-sport into the recreational and by extent also into the long-distance sailing and cruising. Traditional long-keeled, heavy displacement ships are a rare exception in marinas and anchorages today.

Nowadays, the majority are almost-no-displacement large surfboards with a long keel attached in the middle and one or now more often two skeg rudders that are hung from single points somewhere at the end of the boat. Developed for high speeds during focussed racing, this seems like an odd choice for cruisers - like taking the lowered Racing-Porsche for the family vacation instead of the comfortable Mercedes-Limousine. This comparison works as well for the load that they can carry – four suitcases in the Porsche will have a drastic impact on performance, while four suitcases in the Mercedes will only slightly change handling characteristics. The same with boats. A ton of stuff loaded onto a heavy displacement ship will make it a little slower (seven instead of eight knots) and barely effect handling, while a ton of stuff on a racing-cat can cut performance in half (nine knots instead of eighteen). Long-keeled, steel welded NAILAH has a canoe stern and a flush deck in front of her small aft-pilothouse. The almost 16ft or 5m wide flush-deck is not only great to transport the dinghy while it is inflated, but provides lots of room to repair sails, and it also gives a very safe feeling when one has to go forward in heavy weather. But in order to still have enough headroom and standing height below deck, NAILAH´s draught is almost two and a half meters or eight feet deep, making many anchorages and even some marinas off limits to her. A price to be paid for seaworthiness and sea-kindness.

Sea-kindness is the gentleness in the way a boat will move when it rocks and rolls, and it is not something inherent to all monohulls, but a long-keeled, heavy-displacement monohull like NAILAH with her substantial weight and length will pitch actually a lot less than a multihull of the same size, and she will do it in a very slow and gentle manner. Since cruisers tend to sail in front of the wind with following seas, this makes NAILAH very sea-kind with waves from forward or aft – not so much from the side … when it comes to rolling, a mono must rely on its sails to keep her heeled over in order to stabilize this axis, but in weak winds with a high swell this is sometimes futile and the multi is in deed more stable in these conditions.

Apart from half the price of a multi, when it comes to the marina, there is also that little boy in many of us, myself included, that wants a ship to look like a ship and not like a mixture between a bungalow and a bathing-platform.

Isla de San Martino, Galicia, Spain - 2021

For myself and many of the cruisers, liveaboard sailers and passage makers I talked to in recent years, it was all beingsurprisingly easy to do, after this initial decision to actually do it.

It all starts with a dream, a vision or longing for some undefined freedom that might finally be found, once one reaches the horizon. When moving onto NAILAH permanently, I was looking for sailingsongs to take with me and was surprised how many artists in the past 50-70 years felt compelled to write a song called “Sail away”. Sometimes as a proposal or recommendation, sometimes as animperative or last resort. This seems to show that the romantic dream of seafaring is still alive and well.

The one important and most difficult decision is the initial decision to buy a boat and to sail away on it, because this is the one decision that nobody can help with.

NAILAH showing Colin Archer’s perfect form - the form of classic life-boats

After this, all other decisions are not that hard to make, because they can be helped to become informed choices. Then all one has to do is listen to the old salts who are going to recommend a boat that even non-sailors are going to recognize as seaworthy, and not fall for the flashy sales-catalogues that try to sell a large, shiny fashion accessory to a sailor’s wife or spouse … if planning to go far out there, choose wisely, please.

For further reading on the details and as great help to find a safe boat I highly recommend John Vigor’s book “Seaworthy Offshore Sailboat” ISBN 978-0-07-170607-0.

Leave a comment